- Home

- Melissa Maerz

Alright, Alright, Alright Page 6

Alright, Alright, Alright Read online

Page 6

Then one day I ran into him, and he had an 11-inch-by-17-inch piece of paper with a bunch of notes. I didn’t know much about film, but I knew that a film script didn’t usually look like that.

Richard Linklater: In a 24-hour period, I sat down and wrote the whole road map to Slacker, from five years of notes I’d been taking. I figured out the baton passes between the characters. Only some of the scenes had dialogue, but that wasn’t the first order of business. The first order was the flow of the story.

John Slate: The structure of the film is what’s kept it fresh all this time, the fact that it’s 24 different scenes. The film’s been compared to the 1950 film La Ronde, because that’s also a series of stories that run into each other, where one character from one episode walks into the next one.

Chale Nafus: [Robert] Bresson was one of Linklater’s favorite filmmakers, and Bresson’s 1983 film L’Argent was about a 50-franc note that passed from person to person, from scene to scene. Slacker is very reminiscent of L’Argent in that regard.

Richard Linklater: My money was long gone, but I had credit cards, so I used them to buy anything we needed for the movie. It became a credit float, which I couldn’t pay. I went into active debt. That’s really risking the rest of your life. I don’t know what I was thinking. Maybe I thought, “Fuck it, maybe I’ll just declare bankruptcy.” I just knew I had to finish the movie.

Gary Price: There wasn’t GoFundMe or Kickstarter or any of that stuff. You had to figure out how to fund it. And who wants to fund an off-the-wall movie? I “invested” $1,000. I offered Rick more, and he wouldn’t take any more. I don’t think he wanted any one person to control too much.

Richard Linklater: I had seen my sister Trish get married, and then she got divorced a couple of years later. So there I was, in my late 20s, telling my parents, “You know those thousands of dollars you paid for Trish’s wedding? Well, you could just give me that money for Slacker. Think of it as the marriage I’m never going to have.” That was my pitch, and it worked. And I still haven’t had that wedding.

Don Howard: For many years, the only equipment rental house in Austin was a place called Deer. It was owned by this guy Richard Kooris, and it only had two employees: Lee [Daniel] and one other guy. Richard Kooris told Lee that any time someone’s not using the equipment, you can borrow it. So Slacker had a truckload of professional equipment. That’s important when you think about it. The movie is funky, but it still looks like a real movie. Slacker wouldn’t have happened without Lee.

Kal Spelletich: We all worked for free. The irony of all that was, real slackers wouldn’t fucking show up for three days of work for nothing but old bagels and some cream cheese.

Don Stroud: Slacker was such a hands-on, original, DIY kind of experience. Usually on a film, there’s 180 people in the crew and 10 in the cast. This was like 10 in the crew and 100 in cast.

You know the union phrase, “Time and a half after 10”? You work 10 hours and then your overtime kicks in? Well, Rick and his friends made jokes about that. They said, “We made Slacker in one summer on credit cards, and it was taco and a half after 10.” Because when you got cast in the film, they would buy you a taco. That was your payment. It was a great experience, but nobody thought it was going to be anything.

Richard Linklater: Anne [Walker-McBay] helped me organize casting for the movie, and then, through sheer organizational skills and enthusiasm, worked her way up to production manager, too. Some people work hard and you take it as a sign, like, “Hey, we’re meant to be working together.” I had other friends I thought for sure would step up and fill these roles, and guess what? They didn’t. It was like, “Who wants to work for nothing, on a film that no one will ever see?”

Don Stroud: The auditions were very Austin. You didn’t really audition. You just talked.

Kim Krizan: My audition basically consisted of me telling them about my master’s thesis, which was on Anaïs Nin, the diarist.

Teresa Taylor: I was under the influence of crystal methamphetamine when I auditioned.

Jay Duplass: Slacker starred real people you’d see on a daily basis around town, because Austin was such a small place at that time. Rick put them in the movie because he liked how weird they were, and because that was part of the ethos of Austin at the time, this fierce independence as to who you are and what your point of view was. Rick would talk to these people, and then he’d be like, “Hey, could we have this conversation on film, on Friday, with this other character?” And he’d write a scene around them.

Chale Nafus: One night, I went to Rick’s house to see a film of some sort, and this fellow was there. My friend George Morris was like, “There’s that asshole who talks about UFOs!” And then this fellow ended up in Slacker, talking about UFOs.

John Slate: The discussion of “Conspiracy A-Go-Go” in the movie is funny because that was a real publication I’d worked on. It was the 25th anniversary of the JFK assassination, and I had friends in Dallas that I visited regularly, and we realized that there was kind of a vacuum in Dallas for JFK-related tours, so we concocted our own humorous tour and produced a little booklet to go with it called “Conspiracy A-Go-Go” that we would give to attendees.

Teresa Taylor: Rick knew that I was the biggest Madonna fan in the world. When I heard about John Hinckley’s desire for Jodie Foster and his plan to kill Reagan for her, or how Mark David Chapman waited outside John Lennon’s apartment and got his autograph and then killed him, I thought, if you want to be viscerally attached to someone in the media, that’s one way for your name to go down in history with the person you love.

So I said in an interview, “I love Madonna so much, I just want to kill her.” I was joking, but I wanted it in quotes. And then Rick was like, “She’ll do the Madonna Pap smear part in the movie!”

Kal Spelletich: I was my character. I was the weirdo media artist guy who sat around and videotaped everything on TV, trying to figure out what to do with the stream of media that really was poison. So, in that scene, I’m talking about that, and I’m surrounded by TVs. That was my studio.

Rick had given me this script, and I was like, “What the fuck? I’m not gonna memorize these lines.” At that point, I was chain-smoking weed, so my short term memory was fried. So I typed up my own script, 10 minutes before we were gonna shoot, and D. showed it to Rick, and to Rick’s credit, he sat there with me and D. and he let me essentially rewrite my whole scene.

Richard Linklater: Kal’s scene is actually one of the most faithful to the original script. But after hearing some others had a hand in rewriting or originating their scenes with me, I don’t think anyone wanted to be the one who’d done basically what was in the script.

Tommy Pallotta: The interesting thing about Rick’s process is that even though he didn’t have a traditional script, by the time they were shooting, everything was completely scripted. He makes sort of an outline, a conceptual idea, and then he talks to the actors, and then there’s a lot of rehearsal. A lot of people don’t realize it, but there’s not a lot of improv in his movies. All the improv happens before the cameras start rolling, and then everything is scripted almost to the letter. And he’s worked that way ever since.

Douglas Coupland: At one point, I met the people from the movie, and I thought they were the most entertaining group of people I’d ever hung out with. They all had theories. Maybe that’s just Texas. People in Texas are a little bit crazier than elsewhere.

Gary Price: Reagan had started defunding mental hospitals in the ’80s, so that was definitely a big presence in Austin at that point. Austin had a legendary mental hospital, Rusk State Hospital. That’s where they sent [psychedelic rock musician] Roky Erickson. So you’d see people like that around.

Richard Linklater: Slacker is the great portrait of Austin in the depression-era late ’80s. Texas was in a huge financial slump. Oil prices had dropped. There were boarded-up buildings there, which is great, because you could get away with anything. We would just pick a corner, set

up dolly track, pull up our little shitty van, and we’d shoot a scene all day, and no cop would come around and ask for a permit. Some onlooker might come around and say, “Hey, what are you guys doing?” And we’d just lie.

Tommy Pallotta: If anybody asked, we said we were making a mayonnaise commercial. Just something that would not interest anybody, not bring any expectations. When I saw the first cut of Slacker, I thought, This is a great time capsule. I’ll look back at this 20 years from now and be glad we had this. But it was hard for me to understand that people outside Austin would be interested.

Scott Dinger: Austin was really a character in the film. So much of it was just about walking around, getting a feel for this really unique place that came out of a mix of cosmic cowboy culture, rednecks, and hippies. I think that weirdness was fueled a lot by the music scene, and also by these students that came from all over Texas to go to UT and never left.

Bill Daniel: Slacker is loaded with Austin references. 709 is one of those things that points to Austin’s counterculture.

Richard Linklater: There’s a famous Austin band called the Uranium Savages, a performance-art rock group in the ’70s. They had a thing with 709. It was just a talismanic number. The rumor always had it that Nixon, who they hated, resigned at 7:09 p.m. central time. You’ll see 709s floating around in Uranium Savages posters, or in certain music venues that are long gone. It became a joke between all of us. I think we put it on a house in Dazed. We made an address out of it. In A Scanner Darkly, it’s everywhere.

Bill Daniel: At one point in Slacker, Louis Black is eating at the diner, and he’s saying to somebody there, “Quit following me.” In that shot, there’s a sign behind him that says “Plate o’ Shrimp: $7.09.”

Richard Linklater: I give Lee, Anne, Clark, and D. a lot of credit for even thinking Slacker could be a commercial movie. Once we were done, I had low expectations. But they were going, “No, I think we’ve got something here.” They were highly invested in it, because they’d put in their time. They weren’t going to just let it go.

Kevin Smith: Rick showed Slacker as a work in progress at the IFFM [Independent Feature Film Market] in 1989.

Chale Nafus: After that, he sold Slacker to a German TV show [for $30,000] and got some of his production money back.

Richard Linklater: When German tourists started coming by the Fingerhut, I knew it was time to get a new place to live.

Louis Black: I had no expectations for Slacker. I was invited to be in it and I almost didn’t go. When Rick gave me the finished film, I fast-forwarded through it, and I watched my part. It wasn’t until someone wrote a review for the Chronicle that I thought, “Wait a second. This movie is about something?” We ran that review on the front page.

EXCERPT FROM SLACKER REVIEW BY CHRIS WALTERS

Austin Chronicle, July 5, 1991

Few of the many films shot in Austin over the past 10 or 15 years even attempt to make something of the way its citizens live. Slacker is the only one I know of that claims this city’s version of life on the margins of the working world as its whole subject, and it is one of the first American movies ever to find a form so apropos to the themes of disconnectedness and cultural drift.

Scott Dinger: Back then, the Chronicle was how everyone would get their information. Local reviews would make or break a smaller film that didn’t have that marketing push from Hollywood. And the review from the Chronicle was four out of five stars.

Tommy Pallotta: I sold the tickets the night it premiered, because I was the manager at the Dobie. Scott Dinger, who owned the Dobie, wasn’t sure how it would do, so initially Scott made a deal with Rick and said, “I’ll take half, you get half.” And then it opened and it sold out like crazy.

Scott Dinger: Slacker was bringing in people that normally would never come to the Dobie. This was an older crowd. Some people would come out scratching their heads.

Holly Gent: I went to Slacker at the Dobie, and as I was walking out, [Texas governor] Ann Richards was also walking out, and she stopped in the lobby and was speaking at large about the movie. She was glowing. She thought it was amazing.

Wiley Wiggins: Slacker was a cultural touchstone. It was super unlike anything else I’d ever seen. It was exciting to see something that came from an authentic place that I immediately recognized as my own community. That was a pretty unusual thing to see on the big screen. I’d seen Giant. I’d seen The Last Picture Show. And when I made associations between Texas and cinema, that’s what I would think of: this grandiose thing that reminded me more of my grandparents than, you know, the kind of people who had been let out of the state mental hospital in the ’80s—which was, like, most of my experience.

Tommy Pallotta: Slacker had been rejected from Sundance when it opened at the Dobie. I don’t think anybody wanted to distribute it. But when it started selling out, people started to take notice. There were articles in Time magazine about “What is Generation X?” And Rick and Slacker became part of that national conversation about a new generation.

Scott Dinger: At that time, there were just a handful of art-house distributors. A director would take a film to a film festival, and that’s where it would be seen and shopped around. Rick must have had a contact to be able to get a distributor so quickly.

Tommy Pallotta: John Pierson is the one who sold Slacker to Orion. He was a producer’s representative, and he worked with Errol Morris, Kevin Smith, Spike Lee—at that time, he was the indie dude. Rick wrote him a letter, and sent him some articles about why he thought Slacker would do well. John’s the one who saw Slacker’s potential.

John Pierson: The initial letter Rick wrote to me lays out how keenly he saw the possibilities of what could happen to Slacker, which showed a really astute awareness of business and what audiences and critics might respond to. I mean, it wasn’t like he said, “I’m gonna be a spokesperson for a generation!” But it’s a sharp analysis of, hey, there’s prospects here.

EXCERPT FROM RICHARD LINKLATER’S LETTER TO JOHN PIERSON

July 23, 1990

We had a screening here in Austin for cast, crew, and friends (about 250) that went great . . . The overwhelmingly positive reaction makes me think once again that Slacker is a definite crowd-pleaser for a particular niche of the population. I’m enclosing a recent Time magazine article about this “twentysomething” audience which I would further define as: urban, educated (anyone who made it past their sophomore year in college), and one that usually reads up on movies before they see them. I feel it can also attract a slightly older audience with beatnik or hippie sensibilities—basically anyone in the entire post–World War II period that has felt at all marginalized or at odds with their society.

Marjorie Baumgarten: Rick never invented the word “slacker,” but he became the spokesman for that generation. There would be all these big debates where people would say, “Oh, but people have used that during World War II, for recruits who weren’t pulling their weight.” But Rick was the one who put that word into everyone’s vocabulary.

Tommy Pallotta: Slacker ended up playing Sundance, and Orion released it theatrically, and it was very with the zeitgeist at the time. Douglas Coupland’s book Generation X had just come out.

Douglas Coupland: Gen X published in March of 1991, and someone had pointed out that three of anything means a trend. I think that the book, Rick’s movie, and I’m not sure what else came up. Maybe grunge? Anyhow, suddenly it was a thing. I honestly never thought anyone would understand the book except maybe 11 and a half people that I went to high school with, so it was like writing something that was effectively invisible. Then suddenly—pop!—it all exploded so quickly.

John Pierson: Slacker was indisputably a theatrical success with $1.2 million box office—$2.5 million today adjusted for inflation—much of that coming from college markets.

Slacker was somehow speaking for an alternative audience. From the moment it caught fire and sold out months of showings in Austin, prior to its pickup and national r

elease, the evidence is pretty clear that Slacker’s audience had been unrepresented and underserved.

Richard Linklater: We got a $100,000 advance from Orion for Slacker, which was so much money, but the film owed money to the lab, and I owed my family and friends. It was a great day when I was able to pay people back, to give them their $1,000, or their $3,000. I paid the whole cast and crew, and myself, but I only netted $6,000. And it didn’t go at all into knocking out my $23,000 in debt.

Teresa Taylor: I never got paid for Slacker when we were making the movie. They were going to take a shorter version of it to the New York Film Festival in the category of short films, and Anne [Walker-McBay] went to Rick in hysteria and said, “I have permission from every single member of this fucking long movie to release their image, but the one I don’t have is Teresa’s.”

I was going to hold out until I got paid. I said, “Everybody at the New York Film Festival mentioned my scene! I’m on the poster! That’s what John Pierson is paying for!”

But D. Montgomery said, “They’ll just chop you out of the film.” I was torn, but I signed the release because, of course, I wanted to be in it.

Richard Linklater: Absolutely not true! Everybody got $100 for each day they worked. Teresa ended up being the poster girl for the whole film, but she worked only about a half day, so she was in the group of the lowest paid. But she was definitely paid, and more than once—everyone who worked one day on it has a proportional piece of it, so we do these disbursements to like 165 different people when we get up to $100,000 in revenue.

Teresa Taylor: About 10 years after Slacker was released, Rick’s secretary called and I was helping her locate some of the stray old actors, so everyone could get their money just before Christmas. I did receive $100 then, just before I appeared on the special features of the Criterion double-disc DVD.

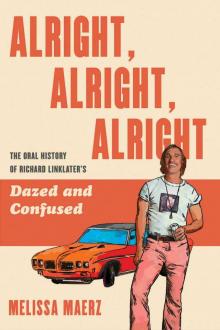

Alright, Alright, Alright

Alright, Alright, Alright