- Home

- Melissa Maerz

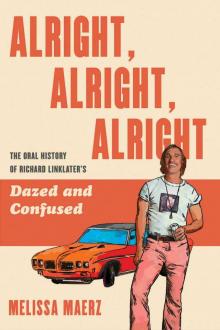

Alright, Alright, Alright Page 5

Alright, Alright, Alright Read online

Page 5

Jay Duplass: Rick knew when college was over, he wasn’t going to be a major league baseball player. The moment you realize that is a big turning point. If you’re into sports, you’re just like, oh, right, there’s a cap on what I’m capable of here. Whereas in other places in life, there are no caps.

Richard Linklater: I never got that major league at-bat. I never did! Every now and then, I think about that, but it took me years to realize I didn’t actually have the right mentality to be a professional athlete. I would never have made it, and thankfully, I didn’t have the opportunity to spend crucial years trying. I did have the right mentality to be a film director.

Brett Davis: I didn’t see Rick again until about six years after graduation. I was going back to Huntsville around Christmas, to the local beer joint, and I saw Rick. I was wearing a Ralph Lauren button-down Polo shirt. It was the Reagan era, and I probably represented everything Rick hated in life. So Rick asked me what I was up to, and I was like, “Well, I went to Texas A&M and I’m going to graduate school, getting my MBA. What are you doing? Did you finish at Sam Houston?”

As you can imagine, this is the period of time where you start to see people you knew in high school, and their paths start to go in different directions, and some of them are not good directions. And by now, Rick had dropped out of college, and he was like, “I’m working on this screenplay. It’s called It’s Impossible to Learn to Plow by Reading Books.”

I was like, “What the hell, man? Dude, you need to pull your shit together!” And, classic Rick, he came at me hard.

He was like, “You yuppie, Beamer-driving asshole! You’re probably one of those dudes who’s going to live behind a gated community or something!”

Driving back after Christmas, I was thinking, “Man, that Rick! I’m worried about that dude. He seems lost.”

Obviously I was wrong as hell about Rick Linklater.

Chapter 3

The Hardest Working Slackers in Austin

“If anybody asked, we said we were making a mayonnaise commercial.”

Richard Linklater and Lee Daniel on the set of Slacker.

Courtesy of Orion Pictures/Photofest.

If you were an aspiring filmmaker during the 1980s, you might have followed an obvious path: go to film school, move to Hollywood, get a job as a production assistant, work your way up through the system. But Linklater always resisted obvious paths. After he graduated from high school in 1979, he went to Sam Houston State University in Huntsville, to study English, but he spent only two years there before he dropped out. It was an unexpected decision, one that no one wanted him to make, he told Reverse Shot in 2004. But, he said, it “set a tone for the rest of my 20s. Maybe the rest of my life. Stay in school was the advice from everyone. I learned early on: listen to all the advice, get a consensus, and then kind of do the opposite.”

During what would have been his junior and senior years of college, he worked on an offshore oil rig in the Gulf of Mexico. He was confident but adrift, smart but uncredentialed. At an age when others were applying for internships and entry-level jobs, he spent his free time watching as many movies as possible. He had planned on becoming a writer until he was about 20: That’s the year he saw Raging Bull, the film he now credits with changing his life and inspiring him to pursue filmmaking. After losing his job on the rig, Linklater moved to Austin with intentions of applying to film school. But he was rejected by the Radio-Television-Film program at the University of Texas (UT), and also by UCLA. His only option was to teach himself.

During his early years in Austin, Linklater discovered a vibrant scene of artists, film freaks, and musicians working outside the corporate world. “The ’80s were a great time to be underground,” he has written. “The natural response to the Reagan years was to just zone out, ignore and withdraw from that ugly/repressive/materialistic yuppie culture that, despite the phony optimism, shades, and thumbs up, was permeated by this cold war apocalyptic undertone. Fuck that—there was this more compelling, hidden from the mainstream, parallel world to enter into, to rejoice in and resist from.”

Linklater’s breakthrough feature, Slacker, captured the ethos of that time. Shot in 1989, when he was still 29, it focused on nameless local characters who didn’t have jobs or aspirations. The plotless narrative was a collection of theories deftly disguised as unconnected conversations: JFK conspiracy arguments, global warming’s relation to space travel, the possibility of a bronze age coming in the ’90s, the commercial value of Madonna’s Pap smear. “Slacker is a work of divine flakiness,” Hal Hinson wrote in his Washington Post rave review. “Perhaps the special insight Linklater has into the muddled psyches of these disenfranchised, mostly white, mostly college-educated kids contributes to the film’s lackadaisical poise. He knows his turf, and he identifies with the unstructured, going-nowhere lives.”

Of course, the man who made Slacker was not a slacker at all. “Rick was the most driven of all of us,” says Teresa Taylor, who played Pap Smear Pusher in the movie. He might not have had careerist ambitions, but he had a singular goal—to make films—and he had a knack for rallying some of his closest friends to help: his roommate, Lee Daniel, the local artist D. Montgomery, and the married couple Clark Walker and Anne Walker-McBay were all part of the crew. “In a sense, we were all slackers,” Clark Walker has said. “Aside from a consuming passion for cinema, what we held most in common was a desire not to work for a living, if work meant doing anything we didn’t love.”

For many people outside Texas, Slacker was a first glimpse of bohemian Austin, long before the South by Southwest Music Festival, the “Keep Austin Weird” marketing campaign, and a national craze for BBQ put the city on the map. To some, it must have seemed as fantastical as a Wes Anderson film looks today. Yet the originality of its perspective translated instantly, connecting with audiences who barely understood what they were seeing. Its pass-the-baton structure—the camera followed one person only until a more interesting one arbitrarily grabbed its attention—aligned with the sensibilities of postmodern moviegoers who’d been raised with remote controls and MTV. And its portrait of the overeducated and underemployed helped establish the Gen X archetype.

Ironically, Linklater wasn’t even a member of that generation: He was born in 1960, a fact he was advised to hide. “When Slacker came out, some publicity person told people Rick was 29, not 30, about to turn 31, because they wanted to be able to say that he was in his 20s,” his sister Tricia Linklater recalls. In reality, he was a natural-born baby boomer, team-oriented and goal-centric. He had always wanted to work with a studio one day. And after Slacker, a studio finally wanted to work with him.

Richard Linklater: When I moved to Austin in ’83, everybody I met was an artist. No one talked about what they did for their day job. They were painters. They were musicians. When you’re in high school, you think the lead singers of bands are rock gods. In Austin, you’d go see them play, and the next day, you’d be at the library and they’d be the ones checking your book out for you. Everybody had ideas. Everyone was writing something. And Slacker really grew out of that energy.

Kal Spelletich: One day, I was riding my bicycle and I hear this roaring racket coming out of my friend D. Montgomery’s house, so I pull over and peek in the front door, and there’s D. on the floor, hunched over all this electronic equipment with Teresa Taylor, the drummer for the Butthole Surfers. They’re making this beautiful, roaring industrial noise sound composition. I knock on the door, and they’re like, “Oh, hey, Kal.” They barely look up. They point to some equipment. I get down on the floor, and we just fucking jammed for two, three hours.

Another time, I’m over at D.’s and there’s a knock on the door, and this young, goofy, pudgy kid comes in the door with a guitar strung around his back and a shoebox full of like 50 Super 8 films. Everyone in Austin was shooting stuff and projecting it on a translucent sheet up in the corner of a room, so I just start projecting the films. I go, “What are these?” and he says, “

That’s my mom,” and he starts imitating his mom. He gets up, swings the guitar around, and starts banging out very simple three-and four-chord songs, kind of narrating the movies that he remembers from his childhood. We go through the whole box of them.

We’re just in stitches on the floor, howling and laughing, helping him narrate the films or just singing along with them, and halfway through it I go, “Wait! That’s [late Austin singer-songwriter] Daniel Johnston!”

This is the kind of stuff that would happen in Austin, especially if you were at D.’s house.

Teresa Taylor: There was a real thriving punk rock community in Austin of musicians and fans, freaks and weirdos, and D. was kind of the ringleader of that. And then there were the cineastes. Rick was a cineaste. Well, everyone was a cineaste.

Deb Pastor: It was a beautiful time. All the different cliques overlapped. If you went to the Black Cat to see live music, the punks were there, the country people, the rockabilly people—all the people were there. If you wanted to know what was going on, you had to actually walk outside and look at a telephone pole with a poster on it, and then you’d go to Inner Sanctum, the record store, and you had to actually talk to somebody. And you’d have heated discussions. If you didn’t agree with them, it didn’t fucking matter. You were still friends, unless someone punched you in the fucking face. What you were thriving upon was all the ideas flowing. And those ideas motivated you to make stuff. That’s how I think of those days. The scene was all about DIY—do it yourself.

Gary Price: Austin was so cheap. Everybody I knew at the time was living in a house where it was like $300, total—to rent the entire house! That’s why Austin had so many musicians and artists. It has the University of Texas, which elevates the intellectual pursuits, but it’s still a lazy place, because you don’t have to make money to live there. People said Stevie Ray Vaughan could play like that because he only had to pay $60 a month in rent. How could he not come up with great songs when he could just play guitar all day and not work?

Anthony Rapp: One of the stats I heard was that Austin had the highest per capita PhD waiters. Because it’s such a nice place to live that people would study there for years, get their PhD, and just wanna hang and stay there.

Jonathan Burkhart: They called Austin the Velvet Rut because it’s so cushy, you never want to get out.

Richard Linklater: When I moved to Austin, I’d gotten laid off from my job, so that qualified me for unemployment. In my two and a half years working offshore, I’d saved $18,000. It was a little disingenuous for me to collect unemployment, since I technically didn’t need it, but that was my “beat the system” ethic. The unemployment checks were my unofficial grant as an artist, whether the government knew it or not. I wasn’t supporting the bureaucracy. The bureaucracy was investing in me.

Now, the bigger question was how I could survive. My trick was to not live like I had $18,000. I had a room in this house in West Campus that was $150 a month, all bills paid. I had a shitty car. And I was like, outside of film stock and processing, I’m going to live on $300 a month, total, for everything. My friends in Austin were like, “Wait a second. You don’t work. You’re not in school. Are you a trust fund kid?” I’m like, “No, I have a savings account.” Everybody had a part-time job, except me, until I had to. I had a pretty good run from ’83 to ’87 when I wasn’t employed.

I had strong ethics about staying out of the nine-to-five grind. Maybe this sounds paranoid, but I think the goal of the greater world is for you to have a mediocre life, not realizing what you want in the world. That’s the story of my parents’ generation. Hardly any of them realized their dreams because they were young parents and fell into the trap of working.

I saw the world as a big trap. I think that’s why I was able to save my money when I was in my 20s. I was buying freedom to live in the kind of world I wanted to live in.

Tony Olm: Rick lived several years in Austin off that money, just going to movies, learning about editing, buying film equipment. He was able to do that because he was good with money. He had journals where he would write, down to a can of caffeine-free Pepsi, everything he spent money on, every movie he saw. He would see 500 movies a year. That was his full-time job.

Tommy Pallotta: I was the manager at this movie theater called the Dobie, and I just started letting Rick in for free. I think he befriended me because he wanted free movies.

Gary Price: We’d go see a lot of movies, and sometimes I’d buy potato chips and Rick would yell at me. “Why are you spending that kind of money?” When Rick was low on money, I would watch him scrape the bottom of an iron skillet with a knife, trying to get enough stuff off to put some flavor onto a tortilla.

Don Howard: I was Rick’s roommate for a summer in an old hippie house right off campus called the Fingerhut. It had this finger pointing upstairs. You can see it in Slacker.

Richard Linklater: It was also called “the Janis Joplin house,” because she had actually lived there.

Don Howard: Rick and our other roommate, Lee Daniel, had very little money, and it was hot as hell. One day I couldn’t get the hot water to come on in the shower and I asked Lee about it and he was like, “Yeah, it’s really hot, man. Rick and I figured we didn’t need hot water.” It was like, “Wow, you guys are hard-core, man!”

Richard Linklater: Lee was my roommate for five years. He was my filmmaking buddy. We bonded over shooting Super 8 films. He had come through the UT film program, and when I met him, he had made an experimental student film—a short—that was really great, and he would come over and I’d show him films I was making, too. He wanted to be a DP [director of photography], but he wasn’t a crazy film buff like I was. I mean, he liked movies, and he was an obsessive camera guy, but he was also kind of a cool skateboard, art guy.

Kal Spelletich: Lee Daniel and Rick were always the anchor tenants at the Fingerhut, keeping the bills paid, but that was where all the film freaks lived.

Richard Linklater: We had a revolving set of roommates. Our front door was broken and thus forever unlocked, so I would come in, and there would be people in my living room. There were always people dropping by, like Daniel Johnston, Gibby Haynes and Teresa Taylor from the Butthole Surfers. You never knew. It was a pretty fun run. People would come by and watch a movie projected on the wall. My first two films came out of that location.

I didn’t really touch a camera until I was 22, 23. Kind of late by most standards. I guess, growing up in Texas when I did, you didn’t think, “I’m going to grow up and be a filmmaker.” It was not an option.

David Zellner: There wasn’t a filmmaking scene in Texas at the time. If you were a New York City person or a California person, it seemed like it was something doable, but it didn’t seem within the realm of possibility outside of that. In the ’80s, I knew about independent filmmakers like Spike Lee and John Sayles and Jim Jarmusch, but they were all from New York. It felt like something far away.

Brian Raftery: Regional film scenes had started popping up. John Waters was working in Baltimore, and that was one of the first times that I remember a really interesting filmmaker being identified with a city he didn’t want to escape. Instead of fleeing your hometown and running to the West Coast or to New York, there was a new idea of staying put and broadcasting your hometown out to the rest of the world.

When you had a movie like Waters’s Pink Flamingos, you were looking at this completely cuckoo version of Baltimore. And George Romero turned the rest of the world on to Pittsburgh in a very strange way. Thanks to movies like Romero’s Night of the Living Dead or Dawn of the Dead, a lot of people’s perception of Pittsburgh was that it was a place where the malls were overrun with either zombie fans or actual zombies.

David Zellner: Occasionally, we’d hear about stuff that was made in Texas, but it was usually people coming into Texas from somewhere else, and it always seemed like it was something from the past.

Holly Gent: There were a lot of Westerns. It was this old guard of cool people

like Bill Wittliff, Bud Shrake, Willie Nelson. The projects were all about, like, “Oh, we got Kris Kristofferson, we got Rip Torn,” or it was something to do with Pancho Villa or Lonesome Dove. I worked on a remake of Gunsmoke.

Jay Duplass: Austin was a very small place at that point in time. If you made films, you made them yourself, and you distributed them on your front lawn. People would have screening parties in their backyards, and other people would record the tape of your movie and pass the tape around and it would get shown at other screening parties. That’s how you got traction as an artist.

Richard Linklater: I had done maybe 20 shorts and an 89-minute Super 8 film on a $3,000 budget called It’s Impossible to Learn to Plow by Reading Books. That taught me a lot. I did it all alone. I was cameraman, I did sound, I edited, I was in it, I wrote it, directed it. I just did everything.

Brett Davis: There’s maybe 50 words of dialogue in his first feature, Plow. It’s just Rick taking a trip on an Amtrak train. But when I watch it now, what I see is a guy who is caught in that limboland a lot of us are in in our 20s, where you’re on the borderline between greatness and homelessness, and you’re not sure which way it’s going to go.

Richard Linklater: When I was finishing Plow, I ran out of money. I needed to pay my rent, so I flirted with a more professional path. At this point, I’m 26, 27 years old. It’s the age where you should be accomplishing something. My mom had a boyfriend, and there was a bullshitty sales job with his company. I went to the interview, thinking, “Okay, I can make a lot more money.” And then it was not a good interview. I was starting to think, I can’t live like this forever.

Tommy Pallotta: I’d heard that he’d made a Super 8 film, Plow, and I was amazed. I thought, “Who the fuck is this dude who’s making an entire feature in Super 8?” I knew people in film classes, and I knew they spent all year trying to get a short film made, collectively. And this guy made a whole feature in Super 8, on his own. I thought, “I really want to know what this guy is up to.”

Alright, Alright, Alright

Alright, Alright, Alright