- Home

- Melissa Maerz

Alright, Alright, Alright Page 8

Alright, Alright, Alright Read online

Page 8

Richard Linklater: Tom thought that’s the best movie ever made. So we were like, great! We will be the American Graffiti of the ’70s. Whatever Tom wants to hear, tell him. And Jim was such a persistent guy. Whenever he talked about Dazed, he was like, “Graffiti, Graffiti, Graffiti!”

Robert Brakey: Sean was the cool guy that didn’t talk that much, and Jim was always talking.

Ben Affleck: He was one of those guys who had one annoying phrase that he would repeat all the time: Like, you know. Like, you know. Like, you know.

Richard Linklater: We seemingly leapfrogged over 35 other projects that were in development. Jim said every time he ran into Tom Pollock in the elevator, he’d bring up Dazed. Knowing Jim, Tom was probably like, “Okay, Jim, if you just shut up and go on location, we might do it, just to get you out of our face.”

Robert Brakey: If they wanted a 1970s American Graffiti, I don’t understand why the guy who did Slacker would be the candidate to do that? Slacker was this nontraditional film that drifted from character to character. The whole point was that it doesn’t have to have a point, and it was so original that way.

Richard Linklater: Unfortunately, Tom Pollock saw Slacker at one point, and he was like, “What the fuck?” He thought Slacker was this weird, arty film.

Jim told Tom, “How do you know Slacker isn’t Rick’s THX 1138? That was George Lucas’s weird art film that didn’t make any money, and he made American Graffiti after that.” Jim could still throw that out as a possibility. You only get one empty promise, until you prove you’re not the next George Lucas.

Tom Pollock: We thought Dazed and Confused would be much more mainstream than Slacker.

Sean Daniel: Because I was the executive on Fast Times at Ridgemont High and The Breakfast Club, Tom said to me, “Come on, get it to be like that!” And it was like, “No!”

Marissa Ribisi: In film, it’s always like, “What’s your big moment? What’s the catalyst? What’s it about?” And I think Rick was like, “It’s not about anything. It’s about people existing.”

If you look at Dazed and Confused, there was the A-story, which is, “Is Pink gonna take the pledge with the football team?” But really, they’re just hanging out. How do you pitch that film? “It’s the 1970s, it’s the bicentennial, the music is gonna be great”? “Here, let me give you millions of dollars!”

Jason Davids Scott: The John Hughes version of the movie is, Pink breaks up with Jodi at the beginning of the movie and has to win her back. And you’d throw up if you had to sit through that, right? Or, like, Tony’s gonna lose his virginity!

Tom Junod: John Hughes movies were about people in high school sort of acting like adults. One of the most beautiful things about Dazed and Confused is that it’s about kids. It’s not like there’s a James Spader character in the movie who is naturally sophisticated and evil. There’s not a patina of sophistication about anybody in that movie. The movie’s villains are kid villains. You almost feel sorry for them.

Brian Raftery: All those ’80s teen movies were frankly about rich kids’ problems. The John Hughes movies were all about idolizing rich kids. When you watch Risky Business now, it’s shocking how much that movie is about going to an Ivy League school and becoming rich. It’s that whole Alex P. Keaton era. I think what made Dazed so appealing was that it didn’t have that weird ’80s ambition hanging over everything.

Jim Jacks: When we finally had a script that we liked, the studio was still like, “Eh, I don’t know . . .”

Richard Linklater: There was a meeting where they get assigned scripts, and they sit in a big room, and they’ve all read the scripts, and apparently in one of those meetings, someone was like, “Why are we even doing this movie?” And Nina Jacobson, who was the executive on that movie, stood up for it.

Nina Jacobson: You can see absolutely why a studio head would say, “Why would we make this independent movie?” It wasn’t a studio movie! But it was an amazing voice, and I thought a studio ought to be in the business of cultivating these singular voices because, in an optimal world, those people become long-term relationships. And the studio that’s there in the beginning has much more credibility later on than the people who all rush over after you’ve had a big hit.

Sean Daniel: Because of my years as an executive, I had a clause [in my contract] that you don’t get in many deals, and which I don’t think anybody at Universal ever got since. I had the ability to, under a certain budget, “put” a picture—as in, I could decide to commit the studio’s money if it was under $6 million. When I started my life as a producer with the studio, there was always the question, what movie would make me put all the chips in the center of the table? And it was Dazed.

Richard Linklater: Sean threatened to put the film, which was big. He ultimately didn’t have to, but he hinted that he was going to do that.

Jim Jacks: There was another studio, Paramount, that was interested in doing Dazed. Universal had to either make it or send it back to us. One of the executives at the other studio was a friend of mine, and she asked to read the script, and she said, “We’d make this. This is exactly what we’re looking for, for our MTV kind of movies.”

Sean Daniel: No studio wants to see a movie they developed go to another studio and then get made. Studios live in fear of that moment.

Jim Jacks: To their credit, Universal decided at the last second they’d make the movie. But they weren’t jumping up and down about it.

Richard Linklater: I don’t think Universal ever really wanted to make the movie.

Chapter 5

Don’t Lead with Your Ego

“When you were making it, it was us, us, us. And as soon as the film comes out, it’s all me, me, me!”

Richard Linklater and Lee Daniel.

Courtesy of Richard Linklater.

Linklater never really wanted to work in Hollywood. When he started crewing up for Dazed, he had already started his own film production company, Detour Filmproduction, in Austin, and his friends who’d worked on Slacker were still around, looking for (and mostly not finding) their next gig. He figured, why not hire them?

Working on Dazed wasn’t exactly what some of his friends had planned. When they were making Slacker, some had assumed their next project would be another independent film, helmed by a different member of the group. “I think our hope was that one of us was going to do a film, then another of us would do a film—we just would all help each other finish our first features in the same semester-based fashion that we learned from college and booking film series,” Slacker’s assistant cameraman, Clark Walker, told Alison Macor, author of the 2010 book Chainsaws, Slackers, and Spy Kids. (Walker and his wife, Anne Walker-McBay, would both end up signing on for Dazed, Clark as second assistant camera and Anne as co-producer.)

Linklater’s roommate Lee Daniel, the cinematographer on Slacker, was surprised that Linklater even wanted to make a coming-of-age film. He confided to Macor that when he first heard about the pitch for Dazed, he thought of Linklater as a “fucking sellout.” Daniel and Linklater had mostly talked about their shared love of European directors like François Truffaut, Andrei Tarkovsky, and Vittorio De Sica, and Daniel thought American high school movies had been done a million times before. “To me we were so much more of a team,” he told Macor. “That’s the way I saw it. He had bigger ideas. He never let on that he was going to do anything remotely Hollywood at all.”

Linklater also thought of that group as a team—but it was his team. And others were starting to see it that way, too. “They had all worked together on Slacker, and Dazed and Confused was a test of that, really: Who could rise to the occasion? Who could let tensions go?” says Macor. “Rick kept his eye on the prize, and maybe that bothered some people.”

Richard Linklater: I didn’t want to go to Hollywood. I was building something in Austin. I couldn’t just leave.

Nathan Zellner: The whole history of Texas being its own country and fighting for independence? That seeps into everything. A lot

of Westerns are set in Texas because Texans are supposed to be go-getters—they’re the ones who tame the land. It’s the same with music. The outlaw country scene in Texas was very much anti-Nashville. Willie Nelson and Waylon Jennings and those guys were like, we’ll go to Texas and we’ll do it our own way. There’s a lot of examples of that. And with Dazed, it was really inspiring to see somebody from Austin making a movie outside of Hollywood.

Nicky Katt: Someone once wrote that Rick treats L.A. like a low-level radiation site. He’ll fly there in the morning, have a meeting, then fly home. It’s like, put on the Hazmat suit, shake hands, then go back to Austin.

Richard Linklater: Well, that’s overstated. Some people just want to go to L.A. and focus on their careers and money and stuff, but I was like, no, I like my cultural life in Austin. I like my friends. And L.A. was not that creative for me. My brain doesn’t work well there.

Bill Daniel: Rick’s dedication to his hometown is really heroic, but it creates its own set of problems.

Chris Barton: Many people in Austin were eager to see what he was going to do next after the successes of Slacker. People were calling the next film Slacker 2: The Prequel or Slackerbabies. Some people needed to assume that this movie was a lot like Slacker, but it was actually very different, especially in terms of budget.

Richard Linklater: The definite upside of working on a bigger film where you can pay everyone is it clarifies the hierarchy and establishes the boundaries along professional lines.

Shana Scott: There was a lot of resentment that Rick got to helm a big studio movie like Dazed and Confused. It was a big deal, because Slacker was a very collaborative effort, and Rick got all the credit. I heard it from everyone.

Kal Spelletich: Look, I love Rick. I am so proud of what he’s done. Having said that, there’s no Slacker without D. Montgomery. D. knew everyone in the movie, and she got everyone to show up for free to work our asses off to make it. And so did Lee.

Teresa Taylor: I always thought that D. was the ringleader, and that her name would certainly be as high or higher than Rick’s on Slacker. See, Rick didn’t know any of the punk rockers. He didn’t know the freaks. He didn’t know the weirdos. D. did. She even came up with the construction of the film: the relay race. You pass the baton on, and who you’re passing the baton to has nothing to do with the person who passed you the baton.

Richard Linklater: My dear friend D. was like, “Hey, all those story meetings, we all had that idea for the baton pass. You didn’t.” I said, “D., I presented the movie to everybody! I didn’t say, ‘Hey, what kind of movie do you guys want to make for the summer?’ I said, ‘Here’s the movie I want to make, and I’ve scraped up enough to pay for it.’”

In every movie I’ve done, it’s like, “Could that have possibly been what you had in mind?” I was like, “It’s exactly what I set out to do!”

Kim Krizan: Some people were frustrated because the script was solely attributed to Rick. A lot of people felt their contributions had been greatly minimized.

Richard Linklater: Slacker was an all-volunteer effort, so I wanted everyone to have a good time, feel a part of it, and invest enough to work hard. Maybe it’s my way of manipulating everyone to do what I want, or maybe it’s my introverted, behind-the-camera personality, but Slacker felt to me like a super subtle benevolent dictatorship. I had absolute final say on everything, and everyone was collaborating with me on every detail, but I always want to be on a team, so I always referred to the film as “our film,” never “my film.” And that’s how I felt.

There’s that great Obama quote about what amazing things can be accomplished if you don’t care who gets the credit for it. You don’t lead with your ego. You sublimate. I was trying to build a community, and I subsumed myself so thoroughly in what I was doing, I didn’t get anything out of making it all about me. By not really taking credit for it in the moment, I left a big piece of the credit pie for others to get a bite out of and feel the time they spent was worthwhile. Cultivating that cooperative team atmosphere wasn’t that hard for me, but I was glad to never have to do it again to that extent. And technically, I couldn’t anyway. The cat was out of the bag.

Slacker getting national distribution and being such a cultural phenom truly freaked out a lot of the people who’d either worked on it or were near it. Especially when it was me, the subtle quiet guy, getting most of the attention. It was classic case of success having many parents. The more some folks thought about it, Why, they wrote everything! In fact, the whole movie was their idea! I remember Lee and D. being like, “Yeah, when you were making it, it was us, us, us. And as soon as the film comes out, it’s all me, me, me!” I’d go way out of my way to give everybody credit on everything. But when they ask where’d the idea come from? I’m telling them. And it wasn’t us, us, us. I’m not going to lie and say, “Oh, I sat around all summer and had no ideas for what the film should be about.” No. I’d been making it in my head for about five years. I knew what I was fucking doing!

Bill Daniel: Dazed was a studio film, and it caused a lot of strife, because a lot of the people in the Slacker group were like, “Wait a minute, I thought we would make a cool art film now. I thought we would make something on Super 8. I had these other ideas of where it was gonna go.”

Alison Macor: Lee wanted to make Hunger after Slacker. It was this Knut Hamsun book, dark and Norwegian. How Lee conveyed it to me was that he felt Rick was selling out. But that’s something Rick has that maybe others in that early group didn’t have: he really had a sense of what could be marketable and what wasn’t.

Louis Black: I’ve always thought, if Rick had done Hunger, right now you’d be saying to everybody, “Hey, let’s go to McDonald’s and visit Rick.”

Alison Macor: Rick told me that he was never that serious about making Hunger and that he and Lee had talked enough about the idea for Dazed that he doesn’t understand why Lee was surprised. And Rick got him a position on Dazed as a DP.

Lee Daniel.

Courtesy of Jonathan Burkhart.

Richard Linklater: Jim Jacks said Lee wasn’t qualified to shoot a studio film. That was probably a given. But he had some good impulses. He’s a gifted cameraman and good at lighting. I remember having to stick up for him.

A lot of people, for their second film, they work with the same DP as the first film, whether he’s good, bad, or indifferent. You do one film together, and you just think, “Okay, that guy’s got my back,” and you’re paranoid that the studio is going to hire someone who’s working for them, not for you. So I tried to bring along as many of my Slacker cohorts as possible, not just for them, but because I didn’t have to question where their loyalty lies. That’s a paranoid way to see it, but that’s where I was at the time.

Alison Macor: Rick had to fight to keep Lee on.

Richard Linklater: As a DP, you’re the head of three departments: grip, electric, and camera. You have a lot of people you need to communicate with and he’s not a good communicator. Besides Slacker, he had only DP’d one other movie, a super low budget black-and-white feature. But we’d been roommates for five years, watched a ton of movies together and had a vocabulary—it felt completely natural for me and I didn’t question it.

Clark Walker and Anne Walker-McBay.

Courtesy of Jonathan Burkhart.

Louis Black: It was a little awkward because Rick made sure the Slacker people had jobs on Dazed, but they were all used to being a collective, and when they all talked it through, somebody was, like, assistant wardrobe.

Richard Linklater: Even as we were crewing up, [production manager] Alma Kuttruff was like, “Do they have a professional résumé?” I was like, “They worked with me on Slacker.” And she’s like, “Uh, so are we talking a must-hire?” I’d just grimace and go, “Yeah. We’ve got to put them in this thing.” I felt I owed these people. I thought that was karmically correct.

It definitely embattles you. It was like, “Okay, you rehired all your friends. Do you know w

hat you’re doing?” I think some of the pros involved saw us as these indie, Slacker amateurs, but we’d all earned it. We were ready.

Bill Daniel: Rick said, “We’ve got an opportunity to do this with studio money. We’re gonna do a real film and do it big, and it’s gonna be great. We’ll still make it weird and make it our thing.”

Richard Linklater: We brought our little Slacker punk spirit to everything we did on Dazed. And then the actors picked up on it, and they had that attitude, too.

(clockwise from left) Joey Lauren Adams, Rory Cochrane, Marissa Ribisi, and Adam Goldberg.

Photography by Anthony Rapp.

Chapter 6

A Truffle Pig for Talent

“We were on the Universal backlot, with tons of people around, and Rory Cochrane busts out a joint.”

No one was making high school movies in the early ’90s. When Richard Linklater began casting Dazed, he called an agent in New York to ask if there were any good teenage actors left. She told him there wasn’t a single one. Teen movies had peaked in the ’80s, thanks to films like The Breakfast Club and Sixteen Candles, but by 1991, even John Hughes, who’d basically invented the genre, had moved on to features that were aimed at a broader audience, and many of the teen stars of the previous decade were too old to play these parts anymore.

Still, Linklater believed there had to be undiscovered talent out there. “There’s no way there’s not tons of interesting young actors in this country—it’s just that not many are big stars yet and agents can’t make a big 10% off them,” Linklater wrote in his “Dazed by Days” diary. “We’re determined to find them.”

He enlisted Dazed co-producer Anne Walker-McBay, who had helped cast Slacker, to search all over Texas for teenagers who might have a ’70s look. He also hired Don Phillips, a loud-talking, name-dropping, vodka-swilling casting director who’d worked on Animal House, Serpico, and Melvin and Howard. Phillips was known for being especially passionate about his work. When studio executives refused to submit Melvin and Howard to film festivals, Phillips remembers, he dropped his pants, cupped his “hairy balls,” and threatened to expose himself unless they relented. The movie went on to win multiple Oscars.

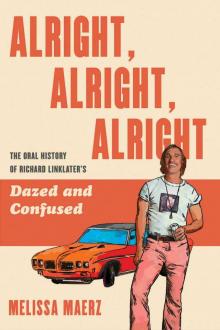

Alright, Alright, Alright

Alright, Alright, Alright