- Home

- Melissa Maerz

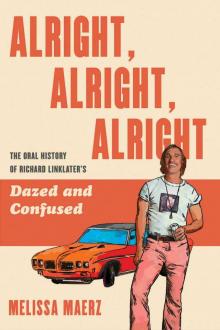

Alright, Alright, Alright Page 2

Alright, Alright, Alright Read online

Page 2

It was 1992 when Linklater started production on Dazed. He was 31 years old. He’d spent most of the previous decade unemployed, with no college degree and a stack of unpaid credit card bills. This had always kind of been the plan. Linklater was a deeply antiestablishment guy who’d never wanted a day job, a marriage, or any of the other trappings he viewed as distractions from making movies. His 1991 breakthrough film, Slacker—a shaggy-dog story about young misfits killing time in Austin, much as Linklater had in his 20s—established him as a major talent and a generational voice, but it also left him deeply in debt. His plan was not exactly foolproof. If Universal Pictures hadn’t green-lit Dazed, he might have been forced to take a far less creative path in the corporate world. This was not only his first shot at making a studio film, it was likely his last.

Once the film came out, the message many people took from it was the opposite of what Linklater had originally intended. There was a disconnect that surprised and sometimes dismayed the director, but in retrospect, after talking to the cast and crew, it’s easier to understand. The cast didn’t actually remember the ’70s. Jason London was four years old in 1976. Wiley Wiggins was born that year. Many of the others—Ben Affleck, Joey Lauren Adams, Parker Posey—thought growing up in the ’80s and ’90s sucked. Once they got past the ridiculous costumes, everyone thought the ’70s sounded kind of great. They’d all end up marveling at the opening scene in Dazed, when a Creamsicle-orange 1970 Pontiac GTO Judge pulls around the corner into a high school parking lot to Steven Tyler’s soaring vocals—“Sweeeeeeeeet!” They couldn’t share Linklater’s cynicism. They likely didn’t even recognize it. How do you open a movie about the ’70s with “Sweet Emotion” and still claim the decade sucked?

Most of the actors had come from New York or Los Angeles. They were shooting in Austin, which felt as exotic as a lunar outpost. Isolated from their friends and family, they grew unusually fond of Linklater, who entrusted them with a level of creative freedom they’d never experienced before and would rarely encounter after. They also grew incredibly close to one another. Some fell in love. Some fell into bed. Some became friends for life—or at least the next 10 years, which is a lifetime in Hollywood. Some still pine for each other decades later. Almost everyone had a blast. And that changed the tone of the movie. They couldn’t hide how much fun they were having, and it bleeds through the screen.

Linklater’s own memories of the summer of ’92 are more fraught. “I gave this introduction to Dazed recently where I said, ‘I’m kinda sick of this movie,’” he admits. “I don’t think it’s my best movie. I think it’s middling. I don’t know why people latch on to it. To this day, I’ll be on a movie set, and I’ll get this little shiver thinking of what I went through then, and I’ll be so happy with how smooth things are going now. I still have PTSD from making that movie.”

Almost from its inception, Dazed and Confused was a war. Linklater fought with Universal over budgeting, scheduling, casting, and tone, and things got particularly heated over the soundtrack. Most artists who battle corporate entities end up with work that’s compromised. What’s crazy is that Dazed was a war that both sides ultimately won. In the face of all logic, Linklater emerged with a movie that perfectly captured the moment-to-moment reality of being a teenager, and somehow also achieved precisely what Universal had signed him to create: a classic film that makes every new audience feel good about the worst time of their lives.

Part I

The Inspiration

Parker Posey.

Courtesy of Jason London.

The hazing scene from Dazed.

Courtesy of Richard Linklater.

(clockwise from top) Deena Martin, Parker Posey, Marissa Ribisi, and Chrisse Harnos.

Photography by Anthony Rapp.

Chapter 1

Oh My God, This Movie Is My Life!

“Am I watching this, or am I remembering this?”

When you think about high school, what do you remember? Regardless of who you were as a freshman or what you did as a senior, it’s nearly impossible not to find something about Dazed and Confused that reminds you of your own past. That’s pretty surprising, considering how closely the film reflects Richard Linklater’s own life at a particular time in a particular Texas town. You might assume the details would be too arcane to translate to anyone else, yet the opposite is true. The year that you graduated is irrelevant. Your hometown doesn’t matter. “This movie is hyperspecific,” says journalist Steven Hyden, “and yet the more specific it gets, the more universal it feels.”

“My whole working premise was that nothing really changes in teenage worlds,” Linklater has said. “There’s a continuum that goes from the entire postwar era through the present day. The dilemmas are the same. The relations are very similar. The pop culture landscape changes, but what it’s like at that age, in relation to your parents, friends, school, that’s a constant.”

Linklater focused not on the things that alienate teenagers but on the qualities that quietly unify them: boredom, horniness, a lack of power, fear of rejection, and the endless optimism that, once night falls, something cool might happen. He knew that you didn’t need to attend high school in Texas in 1976 in order to remember the first time you drank stale beer from a red plastic cup, the first time your mom caught you sneaking back into your bedroom after curfew, or the first time you made out with someone on an itchy blanket. He believed everyone knew a stoner like Slater (Rory Cochrane) and a mean girl like Darla (Parker Posey) and a charismatic creep like Wooderson (Matthew McConaughey). This movie is a period piece, but the period isn’t the ’70s—it’s the period in everyone’s life from age 14 to 17. That’s why so many people consider it their favorite movie, and it explains why it holds up over multiple viewings: everyone who sees Dazed and Confused thinks it’s about them. The experience is illogically personal. We watch it, and we feel what anyone who’s ever been a teenager wants to feel. We feel seen.

Matthew McConaughey: Look, when people go, “What’s your favorite film?” I always have to bring up Dazed and Confused.

Michelle Burke Thomas: Dazed will go down as one of the greats because everyone can relate to it.

Kevin Smith: Every once in a while, as a filmmaker, you think, “Maybe I should make a movie about what it was like when I was growing up.” And then I remember, “Oh, wait, Dazed and Confused exists. There’s no need.”

Ben Affleck: Rick showed the joy, the sense of freedom, but also the profound sense of inadequacy and pain and fear and insecurity of high school. He rang the tuning fork, and it was exactly in tune with a lot of people’s experience.

Richard Linklater: I wanted this teenage movie to play in shitty little towns and malls and drive-ins. I wanted a 16-year-old to stumble into the movie somewhere and see his own life.

Renée Zellweger: I remember reading the script and thinking, “Wow. This is my people. It’s my decade. This is my music. Gosh, if being in this movie doesn’t work out, that’s a big sign that I should just hang it up and call it quits!”

Michelle Burke Thomas: I grew up in Ohio, but it was like, Oh my god, this movie is my life! That opening scene with “Sweet Emotion”? When my sister was a junior and I was a freshman, she took me to my first huge high school party, and there were massive speakers outside and they were playing “Sweet Emotion.” It was just like a scene from Dazed and Confused.

Joey Lauren Adams: I grew up in Arkansas, and that’s exactly how I grew up. We’d cruise around and have keg parties in the woods and listen to Southern rock.

Jay Duplass: In New Orleans, we had our own version of the moon tower. It was called “the lagoon,” and it was in a park, and people would go there to get in fights and make out and get drunk.

Sasha Jenson: Driving around, hitting mailboxes with a garbage can? That stuff is familiar to me. I grew up in the Hollywood Hills, and we’d go up to Runyon Canyon in 4x4s and drive around. We had these giant bumpers, and if there was a stop sign, we’d knock it down.

Bill Daniel: Cruising culture—that’s a Texas thing. I recently stopped in Fort Stockton on a Saturday night and pulled into a Sonic to get something to eat, and there’s a bunch of teenagers hanging out there, just as they have for 40 years. Some older teenagers had their younger brothers and sisters in tow. It was a beautiful thing seeing the older teenagers on one side and the junior high kids next to that. I saw that in the movie, and thought, god, that is so timeless!

Matthew McConaughey: Your car was your identity in high school—that was true. I was a truck guy. I’d get on the PA, duck down in the floorboard and flirt with some of the girls over the PA while hundreds of kids are walking to school. “Oh, look at Kathy Cook’s pants she’s got on today! Nice jeans, Kathy!” Everyone is turning around going, “Who’s saying that?” Then I’d pop up. “You son of a gun!”

Jason Davids Scott: I grew up in suburban L.A., and Dazed and Confused was my high school. Aside from the music that was on the radio. And the cars. And the fashion. And we didn’t do the bullying thing.

Jason Reitman: There’s a specific type of nostalgia that Linklater’s brilliant at, and that’s the tonal nostalgia of what being young feels like. That’s the kind of nostalgia where someone who’s had a completely different life experience watches the film and they still connect with it.

Adam Goldberg: I went to a private college-prep high school in the ’80s in the [San Fernando] Valley, with a bunch of famous people’s kids. It was so different from Dazed. When I saw the thing about the kids getting paddled in the movie, I was like, this is a science fiction movie!

Rory Cochrane: I’m from Jamaica, Queens. There were guys bringing guns to my school and selling crack and throwing kids off of buildings. We had gangs, and they beat people with hammers. That whole thing with the hazing in Dazed? Getting ketchup squirted on you? You wouldn’t try to do that in New York. Some kid would just punch you in the face.

Jason London: None of us had ever heard of anything like that before. There were things that I was like, “Is this true?” And Rick Linklater was like, “This is from my life, man.”

Richard Linklater: Different places had different things, but there was some universal aspect to subjugating others to humiliation.

Wiley Wiggins: My mom got rolled through cow patties in Bryan–College Station. That’s a Texas thing, I think.

Parker Posey: My aunt Peggy had gone through a hazing ritual [in Louisiana] where someone tied a piece of dental floss around oysters and made the girls swallow them and they’d pull them back up.

Steven Hyden: When you watch the movie, it’s like, “Am I watching this, or am I remembering this?” You know the scene in the end when they’re making out and “Summer Breeze” is playing in the background? I’ve never made out with anyone while listening to “Summer Breeze,” but I’ve been in situations that feel like that, when you’ve been up all night talking and there’s all that tension between you and you finally kiss and how amazing that is when you’re a teenager. It’s so sweet and real.

Jeremy Fox: Dazed and Confused is a time piece, but it transcends time. Some films, you watch them a decade later, and they are out of sync with the way the culture is currently. This one is set in the ’70s, but there isn’t a whole lot of stuff in it that isn’t something you would see, day-to-day, throughout different generations. The first kiss when you’re in high school. The first dance. The time you got so stoned, you think a lighter is fucking rainbows and unicorn shit. All that stuff transcends generations. We’re going on about 30 years since the movie came out and it’s still relevant.

Ben Affleck: It resonates with people because a lot of people have a profoundly hard time in high school. For many people, high school is the most stressful time in their lives. And all these neural pathways that are getting laid down stay with you in one form or other for the rest of your life.

Richard Linklater: Everybody has some relation to the high schooler they once were. They’re still fighting the same battles. Or they’re compensating for them. It’s formative shit. I think, with Dazed, I was belatedly working through that stage of life, how odd my town was, how brutal the initiation rituals were. I still don’t know what I think about it.

Heyd Fontenot: I think that’s part of why people still love that movie. We spend the rest of our lives trying to figure out the first 18 years.

Chapter 2

Old People in Your Face, Fucking with Who You Are

“If you’re a nonconformist and an anti-authority person, it’s just kind of like, School’s not gonna be the key to my future.”

Richard Linklater’s yearbook photo, freshman year, 1976.

Courtesy of Kari Jones Mitchell.

Whether you were smart or dumb in high school, a popular kid or an outcast, you probably felt oppressed. That’s the defining experience of being a teenager, and it’s a feeling Linklater captures really well in Dazed and Confused.

When the film begins, on May 28, 1976, summer vacation is starting. These kids should feel free. Instead, everyone feels like they’re being controlled by someone older or stronger or dumber than them. Pink (Jason London) gets yelled at by his football coach, who threatens to kick him off the team if he doesn’t sign a pledge to abstain from drugs. The incoming freshman boys are whacked with wooden paddles by a demented senior named O’Bannion (Ben Affleck). The incoming freshman girls get sprayed with ketchup and mustard by a group of senior girls and their merciless ringleader, Darla (Parker Posey). Even the more laid-back adults kind of treat the kids like prisoners. When naïve freshman Mitch (Wiley Wiggins) comes home late from his first real party, his mom tells him, “This is your one ‘Get Out of Jail Free’ card.”

Dazed might be viewed as a party movie, but when Linklater wrote it, he was still processing some of the less fun memories of his own high school years in Huntsville, Texas. To some people who knew him back then, that’s surprising. He was an all-American kid: a former student council member, a star player in both baseball and football, a promising writer for the school newspaper, someone who was generally well-liked. None of this is lost on Linklater. In the movie, when Simone (Joey Lauren Adams) accuses Pink of acting like he’s “so oppressed,” even though he and his friends are the “kings of the school,” it sounds like Linklater’s poking fun at himself. “In some ways, I was privileged,” he admits. “I was an athlete, I was popular, I was dating. And I’m a white male, for fuck’s sake.”

Still, that didn’t make the worst feelings he had as a teenager seem any less real to him. On July 13, 1992, the day before principal photography began on Dazed, the filmmaker Kahane Corn (now known as Kahane Cooperman) interviewed Linklater for Making Dazed, a behind-the-scenes documentary about the movie. In an outtake from her film, Corn asks Linklater where he’s getting his energy for the project. He says he’s working from a complete teenage mind-set. “It’s as if a 17-year-old was making this movie, with all the knowledge of filmmaking I’ve got, but I’ve cut out all the emotional development in between. So I feel in a pretty weird state of mind right now.”

Linklater felt he was an adult, reflecting from a safe distance on his adolescence. The distance was smaller than he thought. Dazed and Confused would eventually become a classic, regarded by many as eternal and beloved. But when he was making it, he’d have to contend with impatient producers, unimpressed studio executives, and a marketing system that reduced his subtle movie to a series of stoner gags. That same sense of oppression he’d felt back in high school would come to define his experience making the movie.

Richard Linklater: I saw Dazed and Confused as a story about authority trying to rein in youthful passion. That’s what it felt like to be young: there’s old people in your face, fucking with who you are. That’s what growing up is. It doesn’t change much when you’re older, but when you’re on the losing side of that, the disempowered side, it sucks. I guess that was a theme of those years in Huntsville.

Tony Olm: Rick moved to Huntsville, Texas, in fourth grade. His p

arents divorced and he moved there with his mom and his two sisters, Tricia and Sue. Trish was the more social of the two. She was like Mitch’s sister in the movie.

Tricia Linklater: We came from Houston, where we were living out near NASA. My mother was offered a job as a professor in speech pathology at Sam Houston State University in Huntsville, so we left Houston, which was a big city, and we moved to a more rural city. People had cattle, and families owned gas stations and car dealerships. It was a little city with 15,000 people. It literally had one stoplight when we moved there, and a historic main square that had had an opera house at the turn of the century. It was very country.

Richard Linklater: When I moved to Huntsville, it was like going back in time. East Texas is a generation behind.

Tony Olm: Huntsville was very much run by the white folk and the church, and the Baptist churches resisted change for as long as they could, on all fronts. It was kind of stuck in the pre–sexual and political revolutions.

Mike Goins: It was a small-town culture, but it was also shaped by the culture of the prison.

Linden Wooderson: There’s two things to do for work in Huntsville. You’re either involved at Sam Houston State University or with the prison system. It’s the headquarters of Texas Department of Criminal Justice, so there’s tons of prison units.

Mike Goins: When they execute people in Texas, they do it in Huntsville, at the Walls Unit.

Terry Hoage: That was the joke: you would end up in one of two prisons, either the Walls or Sam Houston State. When you went to another town, they’d all ask us, “Oh, did you escape?”

Alright, Alright, Alright

Alright, Alright, Alright